You’re a UK food manufacturer desperate to break into China. You’ve seen all the relevant stats and you’re excited: a population of 1.3 billion people a burgeoning middle class across the eastern seaboard and an increasingly ravenous appetite for added-value Western foods, from infant formula to baked goods and spirits.

In short, you’re certain exporting to China is just what your business needs to take it to the next level. There’s just one snag: you’re a bit nervous about actually doing business in China.

In which case, South Korea would like a friendly chat over some soju and barley tea with you. As Korean specialities such as kimchi, bulgogi and bibimbap are starting to make tentative inroads into the British mainstream, the South Korean government has its eyes on an altogether bigger prize. It is looking to establish South Korea as one of the world’s major food export powers - targeting not Europe or the US but its mighty Chinese neighbour. And it wants British food and drink companies to be right at the heart of its plans.

“The time is right for UK and other European companies to invest in Korea,” says Yeo In-hong, vice minister for agriculture, food and rural affairs.

To ramp up South Korea’s ranking as a global food powerhouse, Inhong and his colleagues are building a $520m, 24 million sq ft “national food cluster” called Foodpolis in South Korea’s western province of North Jeolla - just across the Yellow Sea from China - which it wants to become home to the world’s leading food manufacturers and food R&D specialists, similar to Food Valley in the Netherlands. As a result, by 2030, South Korea expects to be one of the world’s top 10 food exporters and the number one hub feeding Asia and by 2050 it wants to be among the seven biggest food exporters and “a global leader in food R&D”.

It’s ambitious stuff, given how small Korea’s presence in the global food market is at the moment. Food exports account for a tiny fraction of its GDP, amounting to just over $5bn in 2010 by comparison, food exports of its role model, the Netherlands, were 15 times as high that same year [World Bank].

But Korea is pressing ahead undeterred - construction on Foodpolis is starting later this year, and the hub is scheduled to be up and running by 2015. To date, the Korean government has signed memoranda of understanding with 88 organisations that plan to set up shop there, of which 38 are from outside Korea and 10 are from the EU.

The UK’s Campden BRI - which described Foodpolis as “a major business opportunity for UK companies” at the time - is amongst them, signing an MOU in 2012, and South Korea is now on a recruitment drive to get more British food companies to come to Foodpolis.

“We are well placed to help Western companies wanting to do business in this region. Korea is a cosmopolitan, Westernised environment”

Yeo In-hong

So what does Foodpolis claim to offer UK food companies? In short: an easier, more stable and ultimately more Westerner-friendly environment from which to do business with China, equipped with state-of-the-art R&D, packaging and food safety facilities, and a readymade route to export into China and other markets in the north east Asian region.

“We’re trying to create a very comfortable environment, reducing the risk for companies to come in,” says In-hong. “We are well placed to help Western companies wanting to do business in this region - Korea is a cosmopolitan, Westernised environment.”

While a potential trade pact between the European Union and China is only starting to be talked about, South Korea’s efforts to forge free-trade agreements with China and Japan are already well under way, meaning goods produced by UK companies at Foodpolis could benefit from simpler and more attractive export terms than if they were sold to China straight from the UK.

The Korean government is also making a number of financial incentives available specifically to foreign companies, offering tax exemptions, a free lease on land for 50 years (Korean companies, by contrast, have to purchase the land), and other subsidies.

Read this: Korean food in the UK

With Foodpolis located in one of Korea’s key farming areas and close to major ports, it will become home to a significant number of companies handling raw materials, but the big opportunity for UK and European companies is around adding value, believes Junghoon Moon, a professor at Seoul National University and adviser to Foodpolis. “Korea has excellent facilities for manufacturing food, but the problem is our technology is in many cases still behind European technology. That’s where there’s an opportunity for European food manufacturers to come in.”

As wheat has not traditionally been part of the Korean diet, UK companies with expertise in processing wheat and making bread could find their skills especially sought after, with dairy processing also a key area of interest, Moon adds.

With South Koreans’ palates more westernised than in other parts of Asia, some British food and drinks companies might choose to target some of their wares at the Korean market rather than purely using Foodpolis as a springboard into China, but there’s no question the much larger Chinese market is the food hub’s main selling point. “The idea is, you take Korean raw materials - or you import the relevant raw materials into Korea - then you add value to it using European technology, and you export the final product to the Chinese market,” says Moon.

Safety concerns

Central to this idea is the premium attached to foods that come with a ‘made in Korea’ label. A spate of safety scares and authenticity scandals - most recently involving the discovery of fox meat in products meant to contain only donkey - means Chinese consumer confidence in locally produced foods (even if they are sold through international retailers) is low.

“Food safety is a major issue in China, and there is an overall perception in China that Korean food products are safer,” says Yang Kim, MD for strategic planning and investor relations at CJ, South Korea’s largest food company and an early backer of Foodpolis.

Of course, South Korea is not the only country to target Chinese consumers with ‘safer’ food produced abroad, but the reputation of its main competitor in the region - Japan - suffered a major dent as a result of the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, with concerns about radiation in Japanese foods still high on the consumer’s agenda.

Read this: Convenience shopping, Gangnam-style

Products made at Foodpolis would be labelled ‘made in Korea’, allowing overseas manufacturers to tap the goodwill attached to the Korean brand. “Having a ‘made in Korea’ label adds high value to food items, which is why exports to China are a very attractive opportunity for us financially,” adds Kim.

Ironically, the prospect of being able to sell ‘made in Korea’ foods into China has meant Foodpolis has also attracted a fair amount of interest from Chinese companies looking to manufacture their goods in Korea (in some cases, using Chinese raw materials) and then sell them back to China at a premium. It’s a scenario that could potentially prove risky for the ‘made in Korea’ brand, should any such goods subsequently become embroiled in a food safety scare.

“Our technology is in many cases behind European technology. That’s where there’s an opportunity for European manufacturers”

But Kim Wonil, director for Foodpolis at the Korean agriculture ministry, insists food safety procedures at Foodpolis will be stringent enough to avoid this. “All manufacturing processes will be subject to Korean rules and regulations, and checks will be very strict to ensure food standards are very high.”

Even if the Korean government can allay concerns about standards slipping as it ramps up foreign investment in its food industry, its ambition of turning the country into a major food exporting power - rivalling its successes in the hi-tech and semiconductor industries - is going to be a big ask. And although Korea is keen to position itself as a more easy-going alternative to China, UK food companies with experience of doing business in South Korea warn that newcomers should nevertheless prepare themselves for some culture clashes. “It was a steep learning curve for us - Korea is still pretty hierarchical and sign-off processes can be torturous,” says one UK industry source.

Having said that, the Korean government is willing to put up a fair wad of cash towards its ambition. Any UK food company tempted by the opportunities would be foolish to dismiss Foodpolis. South Korea’s ambitions for global food export domination may turn out to be pie in the sky - but could equally mark the catalyst for the emergence of the Samsung of the food world.

Need to know: five iconic Korean foods

Kimchi

Nothing short of a national obsession, this fermented vegetable side dish is served at pretty much every Korean meal. Cabbage and radish are the most commonly used vegetables for making kimchi. Traditionally, kimchi was fermented in large pots buried in the ground today, many Koreans have special kimchi fridges at home, which keep the fermenting veg at a constant 3C. With fermentation an increasingly hot trend on the UK restaurant scene in recent years, kimchi has even been available as a sidedish in Wagamama restaurants.

Gochujang

This red, spicy paste is a key ingredient in many traditional South Korean dishes, including the iconic bibimbap, but UK-based importers - such as Korea Foods - are looking to position it more broadly in the British market, promoting it as a an easy-to-use and versatile condiment that can be used to spice up a range of dishes, Korean or otherwise - the chilli sauce of choice for foodies who consider sriracha a bit 2013, if you will. In keeping with Korea’s love of all things fermented (see kimchi), gochujang, too, is made using fermentation.

Bulgogi

Arguably the Korean dish that has made the greatest inroads into British food culture to date, bulgogi is grilled beef marinated in a distinctive sweet marinade made from soy sauce, sugar, sesame oil, garlic and pepper. Although the term bulgogi actually refers to the entire grilled beef dish, it is often used to describe just the marinade, which can be bought ready-made in the UK from specialist retailers and online through Amazon, among others. Meat brand Mariani launched a bulgogi-flavoured jerky in the UK in 2012.

Bibimbap

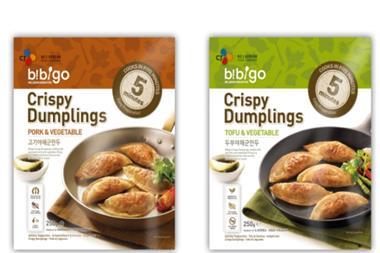

Another of Korea’s trademark dishes, bibimbap is white rice topped with various vegetables, gochujang, and - in many cases - a raw egg and raw beef. It is often served in a hot stone bowl, which cooks the ingredients at the diners’ table (see picture). There are various regional varieties of bibimbap, with the city of Jeonju especially well known for its version of the dish. In the UK, traditional bibimbap is on offer at South Korean restaurant chain Bibigo, owned by CJ Corporation, which opened its first London location in Soho in 2012.

Soju

Often described as the spirit sensation that hardly anyone has heard of, soju is the world’s bestselling spirit and a staple of Korean dining and socialising. It can be made with anything from rice and barley to tapioca and sweet potatoes, and is filtered through charcoal. Traditional South Korean drinking etiquette dictates one must not pour one’s own glass of soju, or risk years of bad luck. The world’s biggest-selling soju brand, Jinro, is available in the UK through Waitrose and Amazon, among others (rsp: about £13.50 for a 700ml bottle).

No comments yet