The stakes are high in booze. The prize pot is huge. Britain’s 100 Biggest Alcoholic Brands are worth £8.9bn, and have racked up an extra £221.8m between them in the past year, a rise of 2.6%, on volumes up 1.6%.

Of course, the higher the stakes, the higher the risk. And there’s no shortage of brands whose luck has run out in the past year. Five have left the top 100 altogether, losing £17.6m in sales between them. To put that in context, just two left the table in last year’s report.

So who has the strongest hand in today’s booze market? Which brands are the top trumps and which are the jokers? And what’s pushed the average price of Britain’s biggest booze brands up 0.9% as prices in the wider grocery market continue to deflate?

Our survey - in association with Nielsen - shows the situation was much rosier a year ago. Combined value sales were up 5%; volumes were up 3.3% [52 w/e 26 April], thanks primarily to a surge in lager, cider and spirits sales during the blistering summer of 2013. The World Cup turned into a damp squib.

Still, at least growth is going in the right direction. And that’s no mean feat in the current climate. A change in the way we categorise brands has also made some appreciably bigger than last year - including Stella Artois (1), the biggest brand on our list - as all variants regardless of sector are now included under each brand (see Methodology p30).

This year’s top-performing brand is a spirit. Smirnoff (2) has overtaken Foster’s (3) thanks to growth of 9.1%, worth an extra £39.5m at the tills, on volumes up 7.3%, boosted by a packaging redesign, hefty investment in marketing and innovations such as Smirnoff sorbets, which racked up £6.5m in the year following their launch in spring 2014.

Other brands flying the flag for spirits are Jack Daniel’s (11), which has realised the year’s third-highest growth of £30.9m, and Grouse (10), which put an extra £24.4m through supermarket tills. Russian Standard (19) is also a standout performer with its 20.9% surge in value sales equating to £18.9m, pushing it over the £100m mark for the first time.

With spirits in such good spirits, it comes as no surprise that Diageo - which owns nine of the top 100 brands - enjoyed the greatest absolute growth of all brand owners, adding £65.8m in extra sales (a rise of 4.8%) on volumes up 3.1%.

Premiumisation

And the key to the spirits category’s growth has been premiumisation. “Premium spirits are seeing double-digit growth, driving total spirits performance, which also demonstrates that people are happily trading up in their purchases,” says Diageo off-trade sales director Guy Dodwell.

The numbers bear this out. The next two biggest-winning brand owners, Maxxium UK and Bacardi Brown-Forman Brands, also specialise in spirits, particularly of the premium variety. Spirits have also contributed the most to the top 100’s overall growth, adding a cool £154m to the tally, an increase of 6.2% on volumes up 5.2%.

Conversely, few spirits can be found among the losers this past year. It’s primarily (but not exclusively), lager and wine brands at the cheaper end of the spectrum that have suffered. Carling (5) is the biggest loser, having haemorrhaged £23.3m or 6.7% of its value as volumes have sunk 5%. Brand owner Molson Coors has a simple explanation.

World Cup pricing levels stuck

“We are trying to drive value ahead of price and there have been some unprecedented levels of pricing,” says Carling brand director Jim Shearer. “The World Cup brought extremely aggressive pricing. What’s been a surprise is that World Cup pricing levels have been maintained. It is indicative of the role retailers see for the beer category right now.”

In short, Carling - along with Foster’s (3) and Carlsberg (4), which have both sustained heavy losses, too - have found themselves unable to compete with the fierce promotions kicked off by rivals for the football in June 2014, and maintained as the supermarkets continued to use cut-price lager as a means of driving footfall and battling the discounters. Indeed, the combined value of the beer brands in the top 100 has risen just 0.1%; volumes are up 1.6%.

“This is not something that’s driven by the brewers,” Heineken UK off-trade MD Martin Porter points out. “A number of retailers have chosen to use subcategories within alcohol to drive footfall - the historical belief is that consumers will go to other stores if they see great deals on alcohol.”

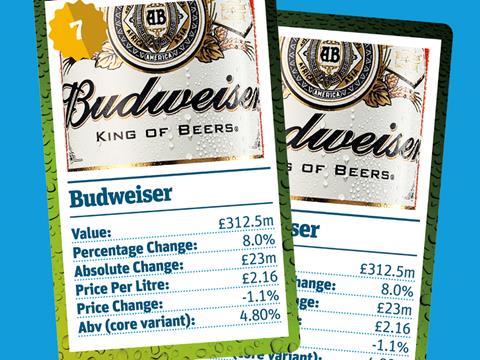

The biggest winner in beer has been AB InBev’s Budweiser (7), which as the official lager of the World Cup ramped up featured space deals during the tournament, contributing to a 1.1% decline in price and aiding the brand’s impressive £23m growth. Sales of AB InBev’s Stella’s premium-strength lager also grew (by £6m), partly as a result of a 2.5% decline in average price.

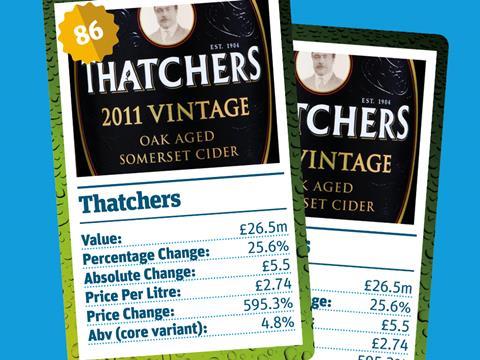

Price, of course, isn’t the only factor in the decline of mainstream mid-strength lagers. The more general trend towards premium strength international lagers such as Peroni (23) and Heineken (41), spirit beers such as Desperados (59) and premium and fruit ciders such as Kopparberg (21) and Thatchers (86) - is also impacting them, though it’s worth noting that some of these premium brands admit greater use of multibuy deals has also been key to continued growth.

Cheaper wine is also suffering, to an extent at least. First Cape (53), the cheapest wine in the top 100 with an average price of just £5.90 a litre, has lost £19.1m over the past year. Meanwhile, pricier wines such as Oyster Bay (49), Villa Maria (54) and Brancott Estate (58) are in much finer fettle.

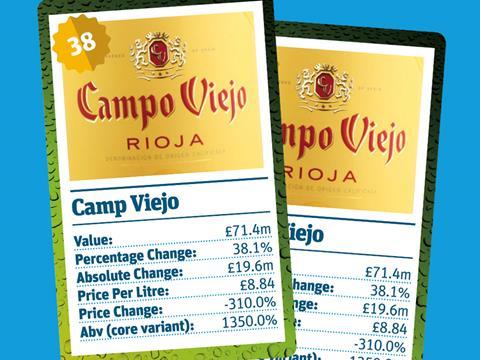

With a portfolio that includes Jacob’s Creek (22), Campo Viejo (38), and Brancott Estate (58), Pernod Ricard is “once again leading the way,” says Pernod Ricard commercial director Chris Ellis, “with the highest average price per 75cl bottle of £6.51 in a category where the average price per bottle has risen by 7p to £5.37. It’s been a really strong year for premium wines and spirits.”

Are pricier brands worth it?

Of course, pricier products do not necessarily equal stonking growth. Glenfiddich (82), the most expensive brand in this year’s top 100 with an average price of £44.14, has suffered a 5.5% drop in value on volumes down 10.7%, proving that drinkers will not swallow higher prices unless brands can convince them they’re worth it. The growth of other single malts such as the slightly cheaper but still unashamedly premium Aberlour (123) is another factor.

So while the market is characterised by premiumisation, the dynamics are far more complex. Many higher-end brands are getting cheaper - for example, Jack Daniel’s price is down 3.3% partly because of deals on litre bottles at key events - luring those attracted by the cachet of a premium name at an affordable price, narrowing the gap between them and value-orientated rivals.

At the same time, some cheaper brands are successfully attracting drinkers by promoting hard and investing in featured space in the supermarkets and marketing initiatives. Take Accolade Wines’ Hardys (6) as an example: fetching an average of £7.02 a litre, the wine is at the cheaper end of the price spectrum and prices have stayed the same over the past year. This, combined with high-profile marketing including sponsorship of English cricket, has helped it net the second-biggest gain of the year, worth £31.1m.

“Clearly when a market is in decline, as wine is, price is likely to be a key lever to drive back growth,” says Simon Lawson, MD of Diageo Wines Europe, whose Blossom Hill (9) has declined as prices have crept up. “We understand these pressures but we also recognise there are ways to offer value beyond price, such as by helping retailers to identify what is the right range and layout for their category plans.”

Wine’s overall decline is partly being driven by drinkers switching to other drinks, such as fruit cider. Despite Stella Cidre losing £4.4m, thanks to declines in the core apple and pear variants, the raspberry cider has racked up £12.3m since its launch in May 2013, making it the most successful alcohol launch of the year. Further proof of fruit cider’s continuing popularity can be seen in the results of Kopparberg and Rekorderlig (70).

Polarisation

Wine isn’t only losing out to cider, however. “The growth of Prosecco is largely fuelled by consumers switching from wine rather than Champagne,” says Moët & Chandon (56) marketing manager Mark Harvey. Indeed, The brand has seen value growth of 6.6% on volumes up 5.4% despite booming sales of much cheaper Prosecco brands such as Valdo (75) and Maschio (103). “The growth in Champagne has been solely driven by premium grand marques as consumers trade up to brands of the highest quality. British palates are definitely more sophisticated as we see growth in the Champagne vintage segment with volume up 13% and value up 12%.”

Further proof of polarisation can be found back in spirits. For example Landmark Wholesale’s Prince Consort (96) range of budget spirits has broken into the top 100 this year for the first time. “The continuing trend towards discounters is attracting attention towards great value, such as own brand, which means consumers are open about their search for great value,” says business development director Chris Doyle.

There’s no shortage of spirits brands keeping prices low or lowering them further to drive volumes. For example, Grouse has netted an extra £24.2m partly by fierce deals at key times of the year such as Father’s Day and Christmas that have seen its average price fall 1.7%. Russian Standard vodka is up £18.9m, thanks in part to its attractive price point.

Some brands reluctant to compete on price have suffered. High Commissioner (51) whisky has experienced a steep decline after refusing to engage in the stiffening price competition in blended whisky, as has Diageo’s Bell’s (15). “Price is important to the blended Scotch category,” says Dodwell. “Consumers are price-sensitive and on average over 70% of blends are sold on promotion in grocery.”

The focus for Bell’s and other struggling blended whisky brands - such as Grant’s (32), which has suffered a hefty decline of £9.5m - will be to compete on more than just price over the coming year by reminding drinkers of their heritage and quality.

“It’s about simply refreshing consumers’ memories and reminding them how fantastic the liquid and the Bell’s brand are,” adds Dodwell. “Grocers will always benefit from stocking brands with heritage that are trusted by consumers and have long standing brand loyalty. The key is to show consumers that value can come in other ways, it doesn’t only have to just be about price.”

Which makes it clear: price is still crucial in British booze, but it doesn’t trump all. Strong brands can be just as powerful. Who has the strongest hand?

The full rankings of Britain’s Biggest Alcohol Brands are available here.

No comments yet