Click here for the full rankings

Drinkers like a good fight. And British boozers have borne witness to plenty lately. For Britain’s biggest alcohol brands are under attack: the fight for shelf space in the supermarkets is getting fiercer, while a new generation of brands chip away at their dominance, luring drinkers out of the mainstream with stories of heritage, provenance and passion.

The punch ups have been spectacular. Carlsberg (7) was dumped by Tesco in October, costing the brand dearly (it’s suffered the greatest loss of the year, losing £69.4m); Stella (1) had more than a third of the value of its cider range wiped out as it lost space to heritage brands such as Westons (60) and Thatchers (73). In February, a new rival to Guinness (25) - which itself has profited from embracing ‘craft’ ale and lager - hit the market. BrewDog, the enfant terrible of ‘craft’ beer, launched Jet Black Heart, ‘revenge’ for Diageo threatening to withdraw sponsorship of an awards ceremony if BrewDog won a gong in 2012 (Diageo later apologised when the spat made national news).

For the first time we can reveal the extent to which these so-called ‘craft’ brands are transforming the market. In addition to The Grocer’s annual ranking of grocery’s Biggest Alcohol Brands, compiled in association with Nielsen, this report also ranks Britain’s 20 biggest craft beer and spirit brands. So who are these brands? What exactly is craft? What impact is the craft trend having on the wider market and its biggest brands? And can the big brands play the craft card?

“Craft is a middle finger to the boring and mass-produced concoctions that were dominating the UK beer market. It’s about focusing on the quality of ingredients and brewing the best beer you can,” says James Watt, co-founder of BrewDog, whose off-trade sales have surged 147.4% to £14.3m, making it Britain’s biggest craft booze player and the 130th biggest brand overall.

“Craft allows us to push the boundaries, develop new brews and experiment with new ingredients. We are not tied to tasteless, rigid recipes produced with only profit in mind. Beer buffs across the globe are demanding a better beer and the bottom line is that corporations with profit margins at heart will never be able to deliver a quality product.”

What is craft?

According to Watt, a craft proposition is determined by a combination of the passion and integrity of the people who make it, and the size of the company that owns it. That makes measuring craft brands difficult, if not impossible.

According to Nielsen client business partner Helen Stares: “Several of our clients will have their own definition as to what a ‘craft’ beer or spirit is; none of them will be the same.” For our purposes, we’ve been pragmatic: drinks must be produced in small batches using traditional methods, but we’ve not ruled out brands owned by multinationals or those whose volumes fall below a certain threshold, as it’s not for us to question the “passion and integrity” of the individuals who make these concoctions.

That Bacardi Brown-Forman’s Woodford Reserve has made number five spot in Nielsen’s top 10 craft spirits ranking and Diageo’s Bulleit Bourbon comes in at number eight shows how alive the multinationals are to the craft movement, however.

“Woodford Reserve isn’t manufactured. It’s handcrafted in small batches,” states the brand’s marketing spiel online. Bulleit makes similar claims: “Bulleit Bourbon is inspired by the whiskey pioneered by Augustus Bulleit over 150 years ago. Only ingredients of the very highest quality are used.”

That’s not a million miles away from the claims made by BrewDog (though Diageo has never driven a tank through the City of London to raise cash, as the Scottish-brewed brand did in 2013 to launch crowdfunding scheme Equity for Punks).

Diageo off-trade sales director Guy Dodwell is “quite clear”: big business can do craft. “Craft isn’t about size, it’s about expertise and care for selection of ingredients and production and packaging processes,” he says. “It’s about brands with character and heritage. We have a really strong group of people here at Diageo who are very focused on making drinks that fit this description and have a strong story.”

Of course, the likes of Woodford or Bulleit are still tiny - joint sales are worth £4.8m, though they are growing at a blistering rate. But as Diageo has shown with Guinness, craft can pay big. It has turned around several years of decline for the mother brand through its Brewers Project range. The brand is up 8.4% on volumes up 9.2%. The Brewers Project beers have contributed £5.8m to overall growth of £7.7m.

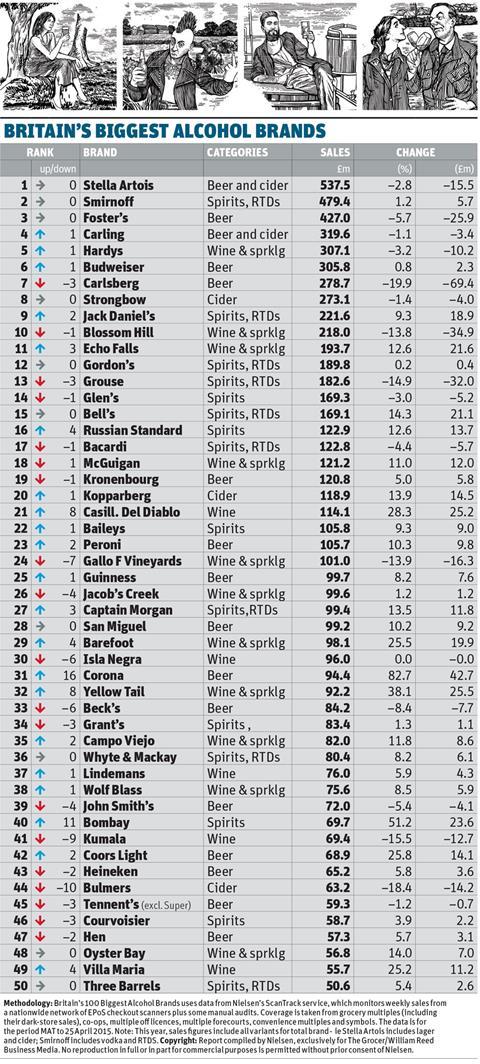

This table shows the top brands 1-50. Feature continues below.

Brewers Project

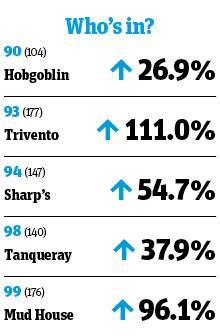

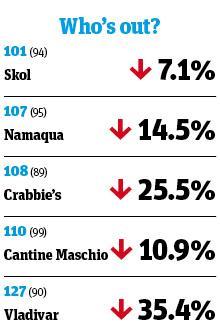

And a glance at this year’s new entrants to the top 100, and those that have left, gives more evidence of how demand for brands that claim to have heritage, quality and provenance is transforming the British booze market. Value vodka Vladivar is out, as is bargain lager Skol, for example; in are Hobgoblin ale (90) and Sharp’s, the Cornish brewer bought by Molson Coors back in 2011.

That deal has been crucial to Sharp’s evolution into a national player. “We’d wholeheartedly disagree with the idea that big business can’t do craft,” says senior brand manager James Nicholls. “In 2010 we were selling 500,000 bottles; we’re now selling 15 million. The brewery employed 70 people; we now employ 144. Our full potential has been unlocked by the acquisition. I don’t know who else would’ve bought Sharp’s or what would’ve happened if venture capital had bought the business. Would they have the expertise and the passion and knowledge to invest in this brewery for the future?”

So Molson Coors’ ownership of Sharp’s has been crucial to the brand’s arrival in the top 100. But it hasn’t been without controversy. Last year, the revelation that Sharp’s bottled ‘Cornish’ ales are in fact brewed in Burton-on-Trent 300 miles away from the brand’s Rock home made headlines. Similarly, craft brewers Meantime and Camden Town came under fire for getting beers such as Meantime London Lager and Camden Hells brewed in Europe at times of peak demand.

That both brands are now owned by multinational drinks companies (Meantime by Asahi, pending clearance; Camden by AB InBev) is significant. In June, Camden MD Mark Turner told The Grocer that the brand’s ownership by the world’s biggest drinks company was playing a key part in its evolution and meant that all production could be brought back to London thanks to investment in a new brewery in Enfield, due to be opened next April.

“This will be a game changer for us in the off-trade,” said Turner, former head of launches at Innocent Drinks. “One of the main reasons we haven’t been so big in the off-trade is because we just haven’t had the capacity. Our turnover for last year was £15m. By 2020 we’re looking to have grown by four or five times that. The bigger retailers like the fact we have the security to grow and build the business.”

AB InBev’s interest in craft isn’t limited to Camden either. “AB InBev’s strategy is to make sure we have a broad portfolio of premium brands that can meet as many consumer needs as possible,” says AB InBev marketing director Nick Robinson, pointing to products such as Goose Island IPA, Leffe and Hoegaarden. “Bigger businesses can do craft; it’s about having speciality products that meet a particular niche market.”

Bigger businesses can do craft; it’s about having speciality products that meet a particular niche.

Bigger retailers will also like the fact that introducing more premium products has the potential to deliver better margins. That’s essential in a deflationary market: the average price of 68 of the top 100 brands has fallen in the past year, indicating that branded booze at knockdown prices is still viewed as a key asset for the multiples in the war with the discounters. With the combined value of the top 100 growing by just 1.7%, or £149m (the lowest rate since 2013), what gains there have been are almost entirely driven by growth for pricier products; volumes are up just 0.3%.

Perhaps the most objective definition of a craft brand is one that fetches a significantly higher price than the market average (smaller pack formats such as the increasingly popular 330ml can have also helped), justified by marketing that trumpets the production processes, ingredients and people behind the products. “Price is important but craft isn’t just about price - it’s about speciality products that have built up a unique story of history and provenance,” says Robinson.

Indeed, most of the brands at the pricier end of the top 100 market themselves along these lines. Glenfiddich (85), the most expensive dram in this year’s ranking with an average price of £43.01 a litre, might not be defined as a craft brand by most drinkers, but its marketing uses the same language, claiming the single malt is made by a family of ‘maverick’ whisky makers. New entrant Tanqueray (98) tells a similar story, with owner Diageo trumpeting the brand’s 180-year history and use of ‘perfectly balanced botanicals’ in the distillation process.

That Gordon’s (12) has barely achieved any growth - value sales are up just 0.2% - in the midst of Britain’s gin boom is also telling. Increasingly drinkers are leaving standard offerings on the shelf and picking up pricier products instead. Four of the 10 biggest craft spirits are gins (see p36-37), and between them they’ve grown by 48%, or £6.6m.

Price is important but craft isn’t just about price - it’s about speciality products that have built up a unique story of history and provenance

Bombay Sapphire (40) has been the biggest contributor to gin’s growth, rising nine places up the ranking on 51.2% growth worth £23.6m, the fourth greatest gain of the year. “Gin is set to keep on rising with predictions of gin sales in the UK reaching £1bn in 2016,” says BBFB managing director Amanda Almond. “Consumers are inclined, more than ever, to purchase premium spirits to enjoy in their own home, taking some of the consumption occasions away from the on-trade. Consumers are drinking quality over quantity, spending more on premium spirits.”

Of course this doesn’t rule out growth at the more value-orientated end of the market. Gordon’s has also lost share to Greenall’s (84), which has achieved a 23.6% surge in sales worth £5.4m, partly as a result of undercutting the market leader by an average of £1.21 a litre (a tie-up with the Jockey Club also helped). Bombay Dry, the value gin launched exclusively into Sainsbury’s in December 2014 and later rolled out to other retailers, has also taken a chunk out of Gordon’s market share, undercutting it by an average £1.34 a litre. Dry’s value has almost quadrupled, with sales hitting £19m.

This table shows the top brands 51-100. Feature continues below.

Nevertheless, the general pattern of premiumisation is repeated across all the key alcohol sectors. Particularly wine. “Some wine brands have struggled with the impact of price competitiveness and range rationalisation,” says Dan Townsend, MD of Treasury Wine Estates, adding that Lindeman’s (37) and Wolf Blass (38) have benefited from trading up. “Wolf Blass has won listings for premium SKUs - for example Silver Label going into Tesco and Gold Label into Asda. Retailers are looking for brands that play a unique role, that hit the right price points and offer something different to the competition.”

Similarly, in lager, standard products are being hit hardest. Stella has seen £15.5m (2.8%) of its value wiped out despite its core 4.8% abv lager racking up solid growth. Stella 4 and the Cidre portfolio are to blame. “Premium brands are growing faster than the standard lager brands,” says Robinson. “That’s not just about world, speciality and craft lager; it’s about premium brands such as the 4.8% abv Stella Artois. Stella 4 has had a tough last 12 months. It’s lost some space on particular SKUs such as 12 and 18-packs.”

Stella Artois Cidre’s decline has prompted AB InBev to redesign the range’s bottle design and to prioritise the bottle format over cans. “Bottles is where we have our highest repeat rates,” continues Robinson. “We’re not going to come out of cans because it’s a reasonable proportion of our overall volume, but the focus is going to be primarily on the bottles in terms of building the brand’s premium nature, consistent with the overall Stella brand value. There is a preconception that cans are cheap but you can do them in a premium way.”

Retailers are looking for brands that play a unique role, that hit the right price points and offer something different to the competition.

With Stella 4 now worth just £21.1m, some industry onlookers suggest the variant’s days are numbered. Of course, Stella’s not the only casualty. Carling (4) British Cider’s sales have fallen £17.3% to £14.4m; Bulmers has lost nearly a fifth of its sales, or £14.2m; Magners is down 11.6%, or £6.3m, and has pledged to refocus on its core apple cider, jettisoning underperforming flavour variants. “The world has gone slightly mad on flavours, and forgotten that cider is all about apples,” says Magners brand owner C&C Group’s COO Mark Boulos. “We’re absolutely focused on apple. Everything around the sides is noise and being delisted.”

With 14 products currently trading under the Bulmers brand - and all but the Blood Orange and Blueberry & Lime variants in decline - brand owner Heineken suggests range rationalisation could be on the cards. “It’s a journey,” says MD David Forde. “We started off with one variant and then pear and then we entered the world of flavours, where you are only limited by your own creativity, but now I have no doubt we are getting to the point where we have overcooked it. There’s been a flavour explosion. As category captains it’s up to us to advise retailers on how we can rationalise ranges.”

Scars

There’s no doubt which brand bears the deepest scars from the rounds of range rationalisation of the past year, though: Carlsberg (7), which has lost 19.9% of its value on volumes down 24.8%, following its delisting from Tesco last autumn. Carlsberg’s loss has been rival standard lagers’ gain, says Forde.

“Foster’s (3) and Carling have gained as a consequence of this,” he says. “It’s still early days of course. When you’re talking about building brands you’re talking about years not months but you certainly don’t want your brand to be delisted from one of the biggest retailers. You have to recognise that there’s a relationship between what happens in the off and on-trade. It’s symbiotic. If you lose distribution in one you can lose it in the other and it can influence what consumers choose.”

Not that either Carling or Foster’s performances are anything to write home about. Carling has gained share in standard lager, with growth of 1.2% but the overall brand’s value has declined 1.1%, due to a combination of factors: the slump in its cider and low alcohol fruit lager mixes; and lower prices on the core lager. Conversely Carling’s volumes are up 4.8%, partly as a result of growing use of deals on larger multipacks.

Standard Foster’s has avoided losses of the scale of Stella 4’s through a combination of lower prices and big marketing (the brand continues its sponsorship of comedy on Channel 4). The core lager has lost 3.6% of its value on volumes down 1.2%, while the overall brand is down 5.7%, a loss of £25.9m. Foster’s Gold and Radler suffered particularly steep declines. Forde says Rocks, the rum-flavoured variant launched in a bid to replicate the continuing growth of tequila beer Desperados (56) has failed to fulfil expectations, hitting sales of £3.4m in its first year.

If any CEO tells you they get it right every time they are bluffing… I’m not sure if some drinkers have been ready to accept a spirit beer in the can format.

“It didn’t do what we thought it would do but it doesn’t concern me,” he says. “If any CEO tells you they get it right every time they are bluffing. With Rocks we were trying to democratise Desperados, which has been a big sales driver at a super-premium price. I think the two rum flavours on Rocks were too close and the abv was perhaps too low and I’m not sure if some drinkers have been ready to accept a spirit beer in the can format.”

Desperados is significant for another reason. Selling at an average of £4.60 a litre it is the top 100’s most expensive beer by almost a pound (the next priciest is Peroni at 23, which sells for £3.76). Yet while this brand is in healthy growth, it’s never played the craft card. Instead it relies on music tie-ups and flavour variants to attract younger drinkers. Its 3.4% gain on volumes up 4.7% proves craft isn’t the only card brands can play.

As does the performance of Corona (31), which has made the greatest gain of the year, of £42.7m. If craft is indeed all about small batch brewing, Corona is its antithesis, made in the world’s biggest brewery and shipped 5,000 miles from Mexico. “It’s roughly doubled because retailers saw the level of investment we had planned for Corona and were prepared to support it,” says Robinson.

Carlsberg, take note.

No comments yet