Crazy-long hours have become a way of life for Rob Tarrant and his team at Brandbank.

As a provider of product data and images for supermarket websites, the Norwich company has doubled its capacity since April, to make sure, when the European Union’s food labelling regulations finally come into force in just over three weeks, that online shoppers at Sainsbury’s, Tesco, Asda and Waitrose can click through to allergen and nutrition information that’s fully compliant.

“I don’t think the legislators gave a moment’s thought to online trading,” says Tarrant. “By April we realised this was going to be tough - and that with every week it was going to get worse. There’s a huge amount to do.”

Brandbank’s work is just the tip of an iceberg that has seen suppliers, retailers, wholesalers, catering companies, restaurants and even European airlines scrambling to bring food and drink packaging and labelling into line with EU Food Information Regulation (FIR) 1169/2011, a gargantuan piece of legislation that was first proposed on 30 January 2008, and which comes into force on 13 December 2014.

The regulations will be introduced in two phases: from next month, back-of-pack ingredient information on all food and drink sold in member states must include allergen and country of origin information in a designated format that meets agreed standards of clarity (see box, p28). From December 2016, nutritional information, including calorie content, will also become mandatory.

It’s not just packaged goods, either. Restaurants and foodservice outlets such as delis, mobile caterers and takeaways must be able to provide the same information about all recipes and ingredients on request. In practice this is likely to mean keeping a folder or database listing the provenance and constituents of every ingredient used in all the dishes on offer. Suppliers that sell food and drink via a catalogue or online must provide the mandatory information before the purchase is made. It’s a situation fraught with difficulty. And compliance won’t come cheap.

Costs

The British Hospitality Association has calculated it could cost the industry up to £200m per year to implement new sourcing and management processes, adapt menus and websites, and regularly brief and train staff. Another estimate from the consultancy firm Campden BRI, in 2010, put the cost per SKU at a whopping £3,280.

“It’s going to affect all the parties in the supply chain,” observes Gary Lynch of GS1, the non-profit organisation that works with major supermarkets and food manufacturers to monitor barcodes and other supply chain management tools.

“The information has got to be on the label and on the website - or in a nutritional book available for customers.”

“It’s barely worth re-labelling most of our old packaging stock. The time involved makes it more sensible to chuck it and start again”

Big retailers, wholesalers and suppliers - with the resource to pay attention to EU diktats, and plan re-labelling as part of normal packaging redesign cycles - have been working for months and even years to be compliant.

Morrisons confirmed last year that it would need to change more than 10,000 labels, while Bidvest 3663, the foodservice wholesale distributor, launched Project Verify, an operation to confirm the provenance and constituents of all the products in its huge offer, more than five years ago.

“It’s taken a whole team an entire year to change the packaging on 15,000 products,” says Bidvest 3663’s head of offer development Graeme Mckenzie.

But there are many more who are not so well prepared, and are in a last-minute rush to redesign packaging. As of two weeks ago, Tarrant estimates just 30% of British products were fully compliant with FIR.

Perilously close

As the Christmas rush approaches, further distractions are likely. “The regulations have come at a time when businesses have been under severe economic pressure,” says Fiona Carter, an independent legal adviser who specialises in food and drink. “Initially compliance may have seemed to be an investment too far in the future, but now the deadline is perilously close.”

In the catering sector, FIR preparations are also lagging behind. “Certainly less than 100% of our customers are aware of the changes, but earlier in the year the figure was closer to 30%, so there has definitely been an improvement,” says Mckenzie.

In recent months, the company has provided foodservice clients with menu templates, workshops, written guidance and an advice centre for queries in an attempt to get them up to speed. “The person who serves the food does not necessarily order it or prepare it but they will need to know the ingredients - or at least have that information to hand,” she adds.

As well as the sheer scale of the changes required, there has been widespread confusion about what exactly FIR stipulates. A key industry complaint is that technical guidance from Defra on the 14 allergens - gluten, molluscs, fish, nuts, milk, mustard, lupin, crustaceans, eggs, peanuts, soya, celery, sesame and sulphur dioxide - that must be labelled and identified as present in food, issued just four months ago in June, appeared far too late.

Brian Young, CEO of the British Frozen Food Federation, reports concerns among larger global players about conflicting interpretations at an EU level. One is over what constitutes the date of freezing in ready meals. “Is it the date on which the fish pie was assembled or when the individual ingredients were frozen? We are pushing for the point of assembly, and Defra supports us. But we still don’t know. And the French and other states have interpreted it differently.”

Conflicting guidance

There have also been allegations of conflicting guidance from the Food Standards Agency and the local authority trading standards officers who will be responsible for ensuring compliance, according to Terry Jones, director general of the Provision Trade Federation. With many local authorities under severe budgetary pressure, they simply do not have the resources to provide advice through their trading standards operations, he adds.

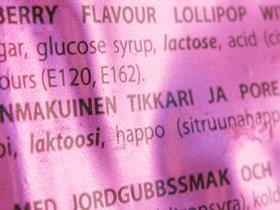

Some global manufacturers have also been hampered by the new 1 .2mm minimum font size, which makes it impossible to list ingredients in several different languages on a universal package.

“One language per pack means shorter runs of different artwork,” says John Corrall of Industrial Inkjet, which supplies digital printing equipment. “For one potential client, a major chocolate manufacturer, this meant run lengths would halve or quarter so they looked at a new digital production system in-house.”

But for many smaller producers left with mountains of non-compliant boxes, bottles and cartons, the FIR is proving an operational nightmare - yet another piece of meddling Euro-bureaucracy that ties British business up in often pointless red tape (see box, above). One company in East Anglia, for example, has just discarded £40,000 of packaging.

“The new regulations are an almighty pain,” says a Scottish cheesemaker who does not wish to be named. “It’s barely worth re-labelling most of our old packaging stock. The time involved makes it more sensible to chuck it and start again. But some of our printed tubs will have to be re-labelled at huge cost.”

Reputational damage

The financial penalties for failing to comply with the FIR will also fall disproportionately on smaller producers, retailers and cafés. The maximum fine for a breach of the regulations is £5,000, imposed by the Magistrates Court, though the most likely response will be an improvement notice rather than a prosecution, according to Laura Scaife of the legal firm Addleshaw Goddard. “This level of fine could have a significant impact on a small family organisation,” she says.

But for household brands the potential reputational damage is a huge factor, she adds. “No retailer wants a repeat of the horsemeat scandal.”

The new regulations will certainly test supply chain visibility. Trusted suppliers will be expected to provide not only accurate information on allergens and ingredients but the provenance of food and drink as well. However, ultimate responsibility for compliance rests with ‘food business operators’ including retailers, restaurateurs and other consumer-facing companies. “It’s no excuse to say the mis-labelling occurred elsewhere in the supply chain,” explains Scaife.

One potentially crucial piece of wriggle room is that only products that have been produced and packaged on or after 13 December are expected to comply with the regulations. In other words, cereal, pulses, flour and other long-life ambient products packed before the deadline can stay on supermarket shelves until their ‘use-by’ date, even if the labelling is non-compliant with FIR.

“It’s possible we will see retailers run down their stock of old labels to buy some time for repackaging,” says one legal expert. By contrast, shoppers can expect to see new-style information appear much more rapidly on meat, dairy, bread and other perishable products.

“Based on the current state of the industry lots of companies will be using these sell-through provisions,” says Tarrant. “In fact for some products the sell-through gap is going to be so large as to be virtually unenforceable to begin with. There’s a chance FIR will be like Y2K: ultimately not a problem.”

But he also believes growing consumer interest in geographical and ethical provenance means providing clear and accurate information could be a key market differentiator for food business operators.

“I worry that we are storing up trouble. Companies will think the job is done but it’s far from over”

“There is a massive benefit for the retailers that get this right,” he says. “Consumers care more and more about the integrity of their products, and they are less and less constrained about where they buy them from.”

However, stating the provenance of pork, poultry and major ingredients that are traded globally presents a real headache to a lot of suppliers, says Young. “If you’re limited in your supply because you have to nominate the country you’re sourcing from you might not be competitive.

Barking mad?

Manufacturers also grumble that consumers themselves appear oblivious of the forthcoming changes, but standard labelling is well intended, says GS1’s Lynch.

“People want to know their food is allergen-safe and their burgers don’t contain horsemeat,” says Lynch, whose daughter suffers from coeliac disease, a severe allergy to gluten. “Lots of EU food regulations appear barking mad but this one is in the right spirit.”

Pippa Murray, founder of London-based start-up Pip & Nut, which makes a range of nut butters, paid about £50 per piece to have all her packaging checked by a specialist food consultancy. “With a nut-based product the repercussions for the business of getting the labelling wrong would be massive, so it was well worth the investment,” she says.

Murray believes that standard EU allergen labelling will help her fledgling company pursue European export markets. “The regulations are clear for producers and consumers who want to understand the product and its provenance,” she says.

Inevitably, the regulations are creating business opportunities for a new generation of consultancies and other companies that facilitate compliance. Digital printers that can produce new labels quickly and cheaply are thriving. “The label guys must have made a killing on this,’ says Lynch.

Traffic lights

One free solution is to use a new app called The Food Labeller, released by Jenny Ridgwell, who has worked in food education for 40 years.

“The Food Labeller has had quite a slow uptake, but I hope that as the 13 December deadline for allergen labelling approaches, more catering businesses will log in to see how it works,” she says. “Allergen labelling is very challenging for caterers who run small businesses and manage cooking and service themselves. There is a lot of work still needed by suppliers to help keep people up to date.”

And, looking ahead, the nutrition information regulations that will come into force two years from now may be another shock for the industry. Food business operators will be obliged to provide information on the energy value and on the fat, saturates, carbohydrate, sugars, protein and salt contents of all products.

“I worry that we are storing up trouble,” observes the Provision Trade Federation’s Jones. “Companies will think the job is done - but in fact it’s far from over.”

The future of the UK’s traffic light system is also up in the air. When the EC first drafted the regulation, it made a provision that national measures over and above the basic statutory requirements would be permitted. However, it is now being challenged by a number of member states on the basis that it impedes trade in the single market.

Given the time it’s taken to persuade some major businesses in the industry to adopt traffic lights, and the cost of implementing them on their labels, it would be a major blow if the EU decides it doesn’t conform with the regulation, not to mention a major embarrassment for the FSA, which has campaigned for them for years. The Department of Health is “very confident” the UK traffic light system will be implemented, however.

In the meantime, the entire industry is racing to be first-stage compliant with FIR 1169/2011. And as anxious calls continue to flood in to the various trade associations, the staff at Brandbank will be burning the midnight oil until the regulations come into force to do its bit. “We’ll be tripling the size of the operation between now and the 13th of December,” says Tarrant. “By the time it comes, we will have earned our Christmas break.”

What the regulations mean for your packaging

Allergen labelling (from 13 December 2014)

Pre-packaged food: common allergens - there are 14 including gluten, crustaceans, eggs, peanuts, celery, milk and mustard - these must appear in bold in the ingredients list, replacing allergy advisory boxes

Pre-packaged food with no ingredients list, such as wine or cheese, must include the word ‘contains’ followed by any allergens

Cafés and all other outlets that supply food without packaging must give information, for example on a menu or a website

Nutrition labelling (the only aspect effective from December 2016)

‘Back of pack’ labelling compulsory on pre-packaged goods

‘Front of pack’ labelling is voluntary, but use of ‘traffic light’ scheme is restricted

Labelling clarity (from 13 December 2014)

Pre-packed goods must display nutritional information per 100g or 100ml

Minimum font size must be 1.2mm

Name and quantity must appear in single field of vision

Misleading labelling (from 13 December 2014)

Information must not suggest food contains an expected component when usual ingredient has been substituted for an alternative

Meat products must declare water content over 5%

Also compulsory (from 13 December 2014)

‘Use by’ or ‘best before’ date

Aspartame and high caffeine content warning

Country of origin labelling (from 1 April 2015)

Country of origin labelling for pork and poultry and for all main ingredients not from country of production

Barmy bureaucracy and euro-meddling: a brief history

1974

E-numbers - Europe-approved additives - appear on British food and drink, referencing colouring agents, emulsifiers, stabilisers, thickeners and gelling agents

1995

EC Commission Regulation No 2257/94 - the “bendy banana law” - specifies bananas must be at least 14cm long and “free of abnormal curvature”

2000

The great British pint is threatened by regulations stating that food and drink must be sold in kilograms and litres as well as imperial measures. It is later dropped

2003

Reports emerge that the British yoghurt will be renamed “mild, alternate-culture, heat-treated fermented milk” - but the proposals falter

2006

The Sun newspaper claims that Bombay Mix must be renamed Mumbai Mix to banish the ghost of British colonialism - but reports prove false

2009

Europe axes rules banning knobbly carrots and odd-shaped turnips from supermarkets, paving the way for “all shapes, all sizes” brands. (Specific rules covering bananas are still in force)

2010

Draft laws insisting that food prices are based on weight threaten to prevent retailers from selling eggs by the dozen. The proposals are quietly dropped

2010

Swedes and turnips are defined as different vegetables - unless the swedes are in Cornish pasties, in which case they are still turnips

2011

Producers of bottled water are banned from claiming that their product prevents dehydration

2014

In December, the first part of the Food Information Regulations finally come into force, to be followed by further regulations on nutritional labelling in 2016

Who’s in trouble?

The industry has only recently woken up to the full implications of the forthcoming FIR, so it is almost inevitable some will be caught napping.

One of the biggest potential problems for food business operators is ensuring the provenance and integrity of their products through lengthy international supply chains. For companies importing from outside the EU, and in particular from the developing world, there is no guarantee of compliance.

“The world food sector tends to be slow to react to legislation,” says Brandbank’s chief executive Rob Tarrant. “Anything ethnic like curry paste and Chinese ingredients could cause problems. Own brand meat products have also been caught on the back foot because there has been lots of consolidation in that particular supply chain.”

For this reason, smaller regional wholesalers without the capacity to run a five-year ingredient verification programme of the type commissioned by Bidvest 3663 are also likely to face problems, according to the company’s Graeme Mckenzie. “Firms that take products in and resell them are going to struggle.”

Retailers with both in-store and web-based operations could also get caught out. Online product information must match the labels on the goods that are picked and packed, but in stores where turnover of long-life products is relatively slow, there might be discrepancies for several months. In the meantime, enforcement officers are expected to target products with a short shelf-life and a very short sell-through provision.

The rapid turnover of menu items, recipes and indeed staff could also cause serious compliance issues for sections of the catering industry, according to Jacqui Grech, policy director for the British Hospitality Association.

“Pop-up or event caterers, establishments with high staff turnover and smaller concerns without the resources to track allergens used in everything from main dishes through to garnishes and drinks could struggle,” she says.

No comments yet