Set up in 2017, the Bright Future initiative aims to provide modern slavery survivors with a pathway back to employment. Now, seven years on, it’s calling on the food and drink industry to help it ramp up its impact

The first time Aisha set foot inside a supermarket was her first day as a Co-op customer assistant. Only months after arriving in the UK from Pakistan, she’d been held captive by a couple that subjected her to abuse, hunger and isolation, forcing her to work unpaid and in constant fear for seven years.

But after social workers rescued her, Aisha was able to begin rebuilding her life. She was provided with safe accommodation and ongoing support, before being asked if she’d consider participating in Bright Future, an initiative designed to provide survivors of modern slavery with employment.

Now, Aisha loves her job in one of the retailer’s northwest stores. She loves the financial independence, the sense of community and the friendships she’s formed with colleagues. Students often flood in from the local college and chat to her. “I feel like I’m a mum there,” she says. “I felt ashamed for a long time. Now I feel blessed.”

Aisha is one of 86 people that have found placements thanks to the scheme since it was first set up by the Co-op and the charity Causeway in 2017, and which now includes many other leading food and drink employers such as Greencore, Morrisons, Asda and Pilgrim’s UK. In January, a new three-year strategy set out ambitious plans to widen this impact more than sevenfold. So, what’s the story behind Bright Future? How does it work? And what will it take to help many more modern slavery survivors in the coming years?

The idea for Bright Future was first conceived amid a renewed focus on modern slavery in UK supply chains, explains Alison Scowen, head of public affairs at Co-op. Two years prior, in 2015, the Modern Slavery Act had come into force, placing a new responsibility on large businesses to address exploitation. And with some 13% of those enslaved in the UK forced to work in the food and agricultural sector, according to government statistics, grocery was under greater scrutiny than most.

Beyond the law

At the Co-op, there was a desire to go beyond what the law required, says Scowen. “We thought, what’s the most meaningful thing we can do as a business?” she says. “We could give the money to a charity supporting survivors. Lots of businesses do that. But one of the most valuable assets we have as a business is our capacity to create employment opportunities for people. That way you can really transform someone’s life.”

This was a missing piece for survivors, agrees Mischa Macaskill, Bright Future Cooperative manager at Causeway. “Survivors were taking really significant steps in their recovery in terms of accommodation, education and qualifications, but they were really struggling to secure stability with employment.”

The retailer began working with the Liverpool-based charity to test the concept of a scheme that could match survivors with suitable work. The process was relatively straightforward. The Co-op identified suitable roles, while Causeway identified survivors that were ready and able to participate. First, a pre-placement meeting allowed everyone a chance to meet in an informal way and survivors to ask any questions and tour the site. Then came an induction and a four-week placement, during which survivors were provided plenty of ongoing support, including regular check-ins to monitor their wellbeing. Throughout, their anonymity was protected from new colleagues. “That empowered them with the decision of how much they’d like to share,” says Macaskill. After the four weeks, they could decide whether or not to accept a permanent contract.

But, straightforward though it may have been, it wasn’t always easy to get right, admits Scowen. “When we first started, we got very excited by some early successes and thought we could do loads of placements but, actually, it’s very hard to do well.

“These are individuals who have been through terrible, traumatic experiences,” she explains. “They may never have worked, or they may never have had a normal workplace experience. We had to take a step back and challenge our assumptions, making sure they understood it was OK to leave at the end of their shift, that it was OK to have a toilet break and that it was OK to phone in sick.”

There was also a need to challenge some of the assumptions of store managers, she adds, and ensure they were fully briefed on what to expect and how candidates may behave or react to particular triggers.

Read more:

-

School and hospital food supply chains ‘vulnerable’ to modern slavery

-

Investors tell supermarkets to tackle increasing risk of modern slavery on UK farms

-

M&S and Tesco among top-tier companies in anti-slavery ranking

Navigating this meant expansion had to be carried out carefully. Six months after launch, Co-op had completed placements for 12 survivors, with a further 18 underway. It began slowly bringing in its suppliers too, among them food-to-go manufacturer Greencore and Pilgrim’s UK.

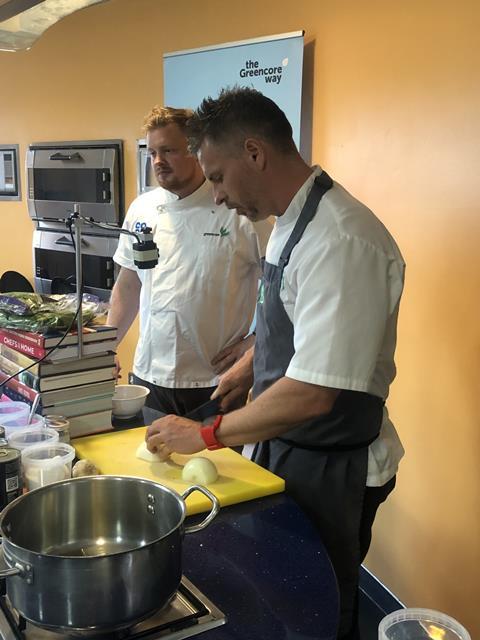

Each placement took a huge amount of consideration, says Ian Siddons, HR business partner at Greencore. Shifts can start as early as 6am, he explains, which meant identifying locations with sufficient public transport. Survivors also had to be comfortable coming into a busy, noisy space, he adds. “It’s an environment that can be challenging if you’re coming from a difficult background, so we had to try to understand those triggers,” he says. “We worked very closely with the support workers at Bright Future and Causeway and, initially, it’s a lot of work settling someone in, walking them around the site and helping them find a role they like.” One candidate was even surprised they were going to pay her for the placement, he remembers.

Pilgrim’s progress

At Pilgrim’s UK, meanwhile, the team has provided 16 placements across four of its sites since 2019, explains human rights manager Andy York. Seven of these still work at the company. “Transparency is key,” he says. “Before placements begin working with us, they come to the site they’re due to be located at to assess if they’d be happy working there for themselves. Language barriers can create issues with integration into the business and local community, so we allocated placements a mentor who speaks the same language and who works in a similar role at their site. We also provided additional advice and support to line managers.”

For all this work, though, the impact is transformative for survivors. “They come in very timid and don’t really talk to anybody,” says Siddons. “Then, within a couple of days or weeks, they’re smiling, they’re talking to people, they’re interacting and they’re confident.”

York believes “the Bright Future scheme provides a chance for survivors to take back control of their lives, give them back their dignity, and help them build a better future for themselves”.

To cement this impact, in 2020 the scheme was set up as an independent co-operative. It now has 34 members, including both its charity referral partners and employers. And in the next three years, it’s looking to ramp up its reach much further. By next year, the organisation plans to provide 100 placements annually, half of which it hopes will become permanent roles. With fewer than 90 provided in the first seven years, it’s an ambitious target – one it hopes to achieve by convincing more UK employers to get involved.

Daunting though it may seem, York would encourage other food and drink businesses to consider whether they can help. “I’ve seen first-hand the transformative impact the Bright Future scheme can have, taking people who have been the victims of modern slavery and exploitation, equipping them with new work and language skills and watching them grow.

“It’s a simple and easy way to provide practical help,” he adds. “All good businesses have vacancies that need filling, and when you see the difference it makes to a survivor’s life it’s very powerful.”

Yes, there are challenges, but “the rewards far outweigh the effort and time that needs to be invested”, echoes Gillian Winters, head of technical at Greencore, who introduced the project to the business. Not only is there “the reward of seeing these individuals go away with a smile on their face and with confidence” but existing employees feel energised by the opportunity to make a tangible difference too. “All our sites have absolutely embraced it, they’re enthusiastic and they really want to do it again. It’s extremely rewarding.” Then there’s the fact that getting involved allows a food and drink business to show they’re going above and beyond, she adds. “It allows you to demonstrate that you are actively trying to deal with modern slavery and not just posting a statement on your website.”

If you are interested in becoming a business partner for Bright Future, please email info@brightfuture.coop

Aisha’s story

“I wanted to kill myself. I thought I should just jump in the water and end my life”

When Aisha first arrived in the UK from Pakistan, she had hoped to find work as a teacher. She quickly began applying for jobs, taking a room as a lodger with a British-Pakistani couple while she waited, helping out with their two children in her free time. But months passed and, with no luck finding a role, her visa ran out and she told the family she’d need to leave.

They persuaded her to stay, promising to help sort out her immigration status and encouraging her to look for cash-in-hand jobs such as cleaning in the meantime.

Then, suddenly, the couple claimed Aisha owed them £20,000 in unpaid rent and forced her to do all their chores and childcare without pay. This carried on for seven years, during which time she was abused, both physically and psychologically, and kept cold and hungry.

“I wanted to leave, but where could I go?” she says. “I had no money, no papers, no family, no shelter. I didn’t think I could go to the police for help. I used to tremble with fear at the thought of what would happen if they saw me trying to leave.

“I wanted to kill myself. I thought I should just jump into the water and end my life.”

Eventually, social workers grew concerned at the conditions in which the couple’s children were being kept and rescued Aisha, taking her to a Causeway safe house. After being given time to recover, she was asked if she’d consider trying out a two-week placement as a customer service assistant at the Co-op via the Bright Future programme.

“I brought two case workers with me, as I was very nervous,” she says. “It was my first interview in this country. I wasn’t sure I would get the job, but it was very informal. I met with the manager, and then he called me to come and get my uniform. I was so happy. After two weeks there was £200 in my account. I couldn’t believe it.”

Aisha then accepted a permanent position. “I was kept away from people for seven years,” she says. “But I had a hunger inside for meeting people, and it’s still there. I love to speak with people. I love my job.”

No comments yet